Punditry is a great thing. Especially when it involves forecasting major economic changes that are expected to take place over years instead of weeks. It allows anyone to be wrong as often as they are right.

So, all pundits are wrong at least half the time. Especially when they venture into the massively unpredictable oil & gas industry.

But I’m going to venture into that no man’s land of punditry and offer some perspectives on how our industry might deal with the serious demand destruction for fossil fuels we’ve seen in response to COVID-19 lockdowns.

We all know that Saudi and Russian oversupply, when combined with Saudi price cuts and projected demand destruction from the pandemic, along with lack of storage, drove spot prices into negative territory.

Since that historic near-extinction event, spot prices have recovered to nearly $37 per barrel and the equities for a number of oil & gas companies have shown strength. Apache’s stock price has trebled and EOG and ConocoPhillips stock prices have nearly doubled.

Oilfield service companies have not been left behind in the rally, with Halliburton up nearly 300% from its lows and Nabors and Patterson UTI up more than 300% each.

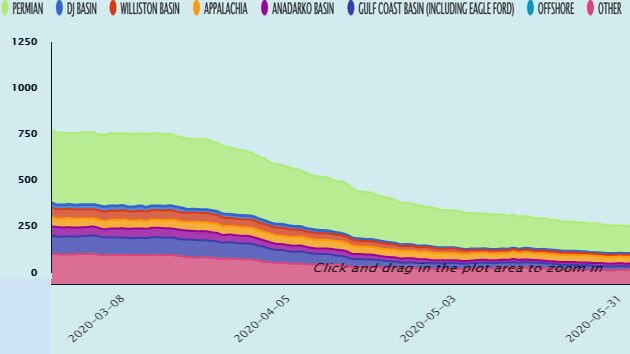

Yet rig counts have continued to fall.

The market is clearly pricing in a recovery to pre-COVID demand levels, but is turning a somewhat blind eye to the cash flow realities that companies now face.

As I’ve pointed out before, however, the prices being paid to producers in the Permian, Oklahoma SCOOP/STACK, and the Eagle Ford are roughly $3-4 per barrel lower than the spot price.

Breakeven spot prices for various basins range from $48/bbl (Delaware) to $58/bbl (Utica)—assuming that the posted prices paid to operators are about $4/ bbl less than the spot price.

Posted prices will have to increase by more than 40%, depending on basin or play, to reach median breakeven levels.

The patchwork reopening of America has fueled optimism that demand destruction of hydrocarbons will be inexorably rolled back as the economy improves. However, if we measure the improvement of the economy by trends in S&P equity valuations, we need to be realistic.

While equities climbed higher from 2014 to their peak in February 2020, spot prices for oil have steadily declined.

So present recovery in the stock market cannot be taken as a proxy for posted price recovery to the levels needed to improve oil & gas margins.

Even though operators have done a tremendous job in reducing costs to improve margins, there’s little added cost saving to be gleaned going forward unless oilfield service companies are compelled to provide even deeper discounts.

That’s not likely given the stress they are already enduring, even if their stock prices are appreciating.

It’s quite likely the industry will have to consolidate in order to stabilize and move forward.

What will this look like?

No one has a crystal ball, but from where I sit, the movement to consolidation will confront several issues.

Scale

Our RS Next solution estimates there are about 65 million gross undeveloped acres in unconventional plays.

Acquisition costs of all the undeveloped acreage at a price of $1,000 per acre would be $65 billion.

Assuming 100 acres per well, and a cost of $5 million per horizontal well—which is probably low—full development cost of this acreage is about $325 billion.

These are big numbers and no company has access to this kind of capital, especially given the cloud of probable bankruptcy filings looming over the industry and the required appreciation of posted prices to achieve even breakeven levels.

In a review of national production done by the EIA for 2018, only about 28% of producing horizontal wells were producing at rates of 100 BOPD or more, which may reduce the number of producing leasehold acquisition candidates.

There will be intense competition for the “best” assets, but a sizable portion of the total available resource may remain on the M&A sidelines.

Timelines in M&A

The universe of company types that operate in unconventional plays ranges from integrated majors to smaller privately-held firms.

Majors are better capitalized—with better access to a shrinking amount of commercial bank credit—and can afford to be deliberate and patient with their M&A strategies. Notably, ConocoPhillips CEO Ryan Lance affirmed that the company was absolutely “on the lookout” for acquisition candidates, but qualified its outlook by saying, “We’re patient. We’re persistent. We monitor the market. I certainly believe there’s going to be significant stress across the sectors.”

This is notable because in the past 16 months ConocoPhillips was a net seller of assets with sales of assets yielding more than $4 billion.

Publicly traded companies without the capital reach of the majors will be in the trading mix, but probably less deliberate in their moves to closing. Many will be caught in the no man’s land of needing to sell assets to provide continuing operational liquidity, but slow to pull the trigger while hoping for a further strengthening of prices to maximize asset sale proceeds.

It’s important to note that modeling the upcoming M&A market must account for the transaction behaviors of private equity (PE), which became large holders of acreage starting in 2015.

PE-backed enterprises—whether publicly traded or not—will probably be all over the map. Companies that deployed cash in the 2013-2015 time frame are nearing their typical portfolio exit door for their funds, whereas PE that came to the party later may still have runway with their funders to be value-focused and patient. Quantum Energy Partners is reported to be raising $5.5 billion to pursue M&A opportunities in this market. VC firm Energy Spectrum Capital closed $969 million in funding to pursue “high-quality midstream assets.”

Workforce

Industry consolidation threatens jobs. Companies acquiring or merging with companies in basins they already operate in will inevitably have asset teams of engineers and geoscientists whose workflows are replicated in the acquired or merged company. In the current “live within cash flow” environment, the natural C-suite response will be to eliminate workforce wage, salary, and benefits expenses.

I would urge companies thinking in these terms to consider a different path.

Task the workforce whose geoscience responsibilities overlap to review and build an inventory of conventional prospects contained in the corporate acreage position.

One of my favorite examples, which I’ve mentioned before, is Pioneer’s discovery of the Sinor Nest field in central Live Oak County, Texas.

The discovery well 42-297-35165 completed a Lower Wilcox channel which was perforated between 8,022 and 8126 feet.

Drilling time was 11 days and when completed, the well flowed at 433 BOPD, 144 MCFD, and zero BWPD.

Before being unitized in 9/2019, this well had produced 586,730 BO and 398,766 MCF, netting approximately $17 million after royalty and severance tax.

After 75 months, it was still flowing at 40% of its peak rate.

The 10 wells completed and reported under lease No. 10786 have produced a total of nearly 3.7 MMBO and 4.7 BCF. Assuming $40/bbl of oil and $2/MCF of gas, these 10 wells have netted about $110 million, at an estimated drilling and completion cost of $20 million (8,200-foot median TD).

They all have gentle decline rates similar to the discovery well.

The best Lower Wilcox well in Sinor Nest field has netted nearly $22 million, whereas the best Eagle Ford well in the immediate area netted just more than $10 million.

The massive amount of seismic and new open hole log data collected in unconventional plays should be valued as the foundation on which to build aggressive interpretation workflows targeted on conventional opportunities.

As climate concerns become more embedded in oil & gas industry strategies (check out the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative), it would also make sense to task so-called redundant geoscience teams with finding mature fields that have reservoirs suitable for the storage of greenhouse gases.

Universities

We have had at least five major pricing disruptions in the oil & gas industry since I first started working for Gulf Oil in 1972.

If, in September of 1979, an incoming freshman had seen the price increase in oil and had elected a geoscience or petroleum engineering major in the expectation that she could profit from this, by January 1986—one or two years into her career if she had pursued a master’s degree—she would be staring into the abyss of an oil market in free fall.

This scenario has been repeated several times and I would guess that many recent graduates are now second-guessing their choice of major.

This is a problem because hiring in the industry has not kept pace with retirements due to an aging workforce. We need new blood to keep our industry moving forward.

Our industry will continue to produce oil & gas for the foreseeable future, but that future will undoubtedly include meaningful steps to address climate change.

Total resource life cycle accountability is an issue that motivates a large percentage of student geoscientists. Companies who will be hiring through this cycle and the next must create positions and career paths that are intelligently funded by more than produced oil & gas revenues.

The future will resolve itself in both predictable and unforeseen ways, but going forward, perhaps we need to flip uniformitarianism on its head and ask, “Is the past the key to the present?”