The US has become the largest producer and exporter of propane. Despite this growth, some parts of the US are still importing the heating and cooking fuel. This dislocation is caused by the Jones Act, a federal law passed in 1920 requiring goods shipped between US ports to be transported on US-built ships and operated by US crews.

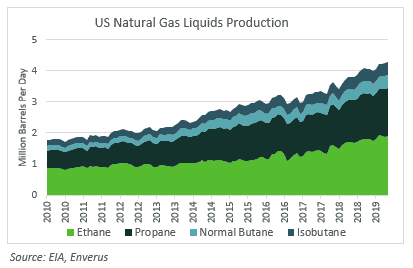

Over the past 10 years, US production of propane and other natural gas liquids (NGLs), such as ethane and butane, has surged, making the US the world’s largest producer of NGLs. Without a concurrent increase in domestic demand, the US has seen a marked increase in exports, becoming the world’s largest exporter of propane. Propane, along with butane, is referred to as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and these hydrocarbons are transported on LPG tankers.

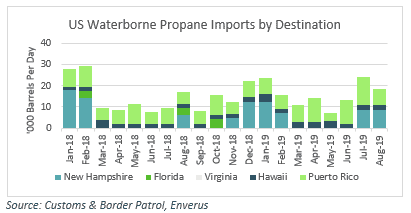

Despite the growth in US exports, some parts of the US are still importing propane. Without any Jones Act-compliant tankers to carry LPG (or LNG for that matter), the only option for Hawaii and Puerto Rico and others is to look abroad. This is also the case for areas without pipeline or rail capacity to deliver the fuel to local markets, such as in New Hampshire. Hawaii and Puerto Rico receive propane cargoes throughout the year to fulfill demand for cooking fuel and other applications, while New Hampshire’s demand is more seasonal, as the fuel has replaced oil for heating purposes.

The observed imports of propane were sourced from a variety of locations. New Hampshire’s Blackline Midstream terminal in Newington sourced propane from Norway and West Africa for its recent imports. Puerto Rico has recently imported propane from Trinidad as well as Equatorial Guinea.

Many customs manifests list their origin point as the Dominican Republic, including the most recent cargoes arriving to Hawaii aboard the LPG tanker Pertusola. The Dominican Republic does not produce a significant amount of hydrocarbons, and those manifests are explicit in that the origin of their cargo is Equatorial Guinea. That cargo was transferred to the Pertusola by the LPG tanker BW Empress, floating offshore of the DR in Ocoa Bay. AIS data from VesselTracker, analyzed by Enverus, suggests that the transfer occurred around June 16, after the Pertusola discharged a cargo from Sunoco Logistics’ Marcus Hook terminal near Philadelphia at the San Pedro De Macoris terminal east of San Juan. The BW Empress is still positioned in Ocoa Bay and is involved in the transshipment of propane from larger tankers arriving from the US and other locations such as Equatorial Guinea onto smaller tankers capable of delivering to ports around the Caribbean. The Pertusola traveled through the Panama Canal and proceeded to Hawaii, where it has since discharged at various islands in the state.

Hawaii’s propane imports are probably the best example of the dislocations caused by the Jones Act in the propane market. Much of the state’s supply in 2018 originated from Trinidad, but production is on the decline in that country. Since the end of 2018, Hawaii has received propane from Argentina as well as cargoes originated in areas such as Equatorial Guinea that were transferred to tankers offshore of the Dominican Republic, similar to the tanker Pertusola mentioned above.

While Hawaii sources propane from offshore West Africa, millions of barrels of US propane are passing by the state every month as they head to Asian markets. The map to the right shows the tracks of tankers loaded with US propane and butane from Enterprise’s Houston and Targa’s Galena Park terminals as they head through the Pacific to destinations in South Korea, Japan, and China.

With no LPG tankers under construction in the US, these dislocations are likely to continue, limiting the ability of US citizens in Hawaii and Puerto Rico, and even New England, to benefit from the shale boom in the same way as citizens of other countries.