These are great times for pundits. We consume so much conflicting data daily; it seems anyone can predict just about anything — proving their point by cherry picking data.

It appears the economy has come roaring back. But has it?

Wage growth has been stellar — at least it seems so when you ignore the fact that recent wage growth is calculated for those still employed, totally discounting those who have lost their jobs.

Home sales are recovering — but only for those who still have jobs and can take advantage of low mortgage interest rates.

We’ve been told we will have an effective COVID-19 vaccine by the end of the year — but, in the name of expediency, that vaccine may not be backed up by normal, scientifically-sound testing and efficacy studies.

The current truths we’d like to organize our lives around all come with inherent uncertainties — so, they’re not really truths at all.

In the oil and gas world, we’ve clung to the belief that a post-COVID world will resume the consumption patterns and continue to drive demand for oil and gas. Hundreds of millions of people in China and India will be buying cars in the next 10 years and cement factories around the world will ramp up production to meet the construction demand for cement.

Remember infrastructure?

We have been promised that the U.S. will embark on an infrastructure modernization program that will restore demand for everything from steel to cement to gasoline.

We have been promised our industry will heal as demand begins to overtake supply.

Some thoughts on supply

In March 2016, the Obama administration slapped sanctions on Russia for its invasion and annexation of Crimea.

The most critically negative aspect of the sanctions, as far as Russia was concerned, was the stoppage of technology transfer to Russia, especially in the oil and gas sector. Although a temporary waiver allowed the joint venture between Rosneft and ExxonMobil to finish one well in the Kara Sea, further investments by any financial, E&P, oilfield service or cloud computing companies are highly constrained. This is impairing Russia’s ability to modernize its oil and gas industry.

Russia needs western E&P technology.

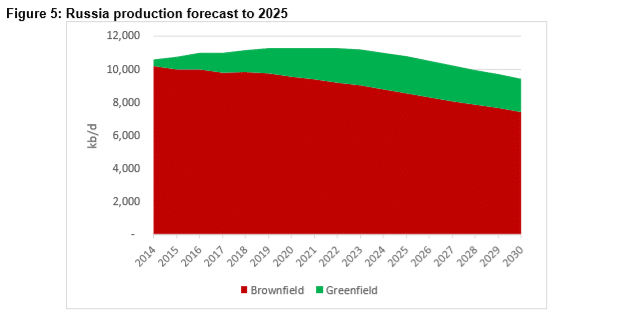

Forecasted production in Russia is expected to stay stable through 2023 at about 11.5 million barrels of oil a day — but this estimate assumes $60-$70/bbl and a weak ruble trading at around 1 U.S. dollar to 65 rubles.

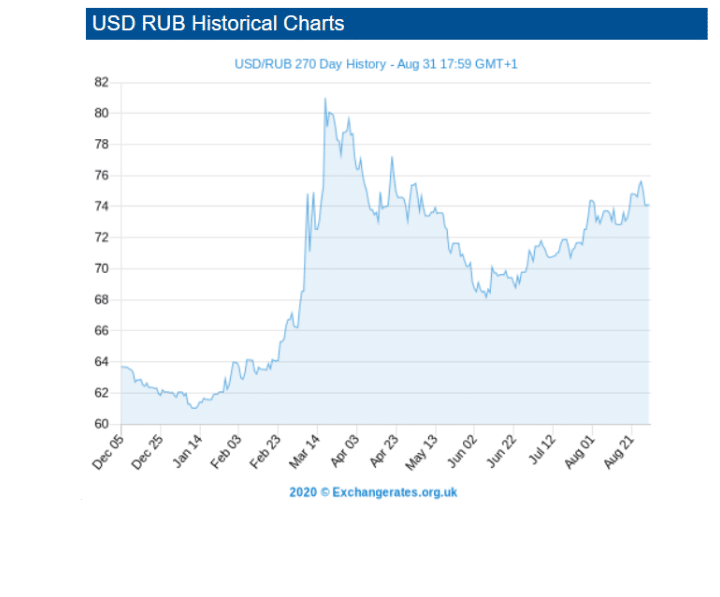

The assumption of a $60-$70 price for Brent is problematic, and current Brent pricing would imply an even more pronounced decline in Russian output. The assumption of a weak ruble seems to be solid, as shown by the chart below from exchangerates.org.uk.

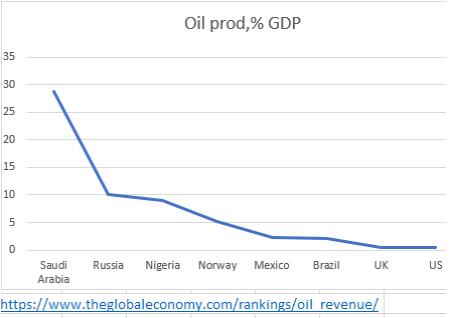

Russian proven reserves are sufficient to meet domestic consumption needs for nearly 81 years, but since oil exports are a significant component of its GDP — 10% (Russia) vs. 0.38% (U.S) — it will continue to need increased production to finance its domestic and international policy aims.

Russia’s biggest potential reserve base is in the Arctic, with some estimates of reserves of barrels of oil equivalent pegged north of 240 billion barrels.

Sanctions, however, cripple Russia’s ability to acquire the offshore technology needed to exploit these reserves, and a weak ruble would make the technology expensive, even if sanctions were lifted.

You could make the argument that President Trump has held off on easing or eliminating sanctions against Russia because it would harm his re-election chances, but that he might consider lifting them if he is re-elected, especially if doing so could be messaged as a job creator for oilfield service and large E&P companies.

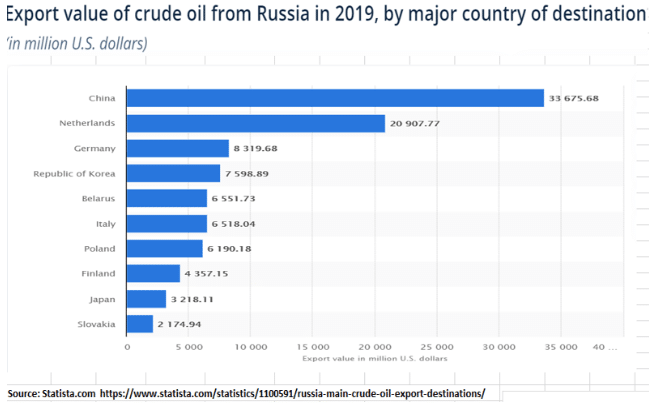

Easing sanctions could benefit larger oilfield service and some large E&P companies, but it would ultimately add dollars to the Russian Federation’s budget for expansionist aims that would probably collide with America’s national security interests, and would ease the economic pressures on rival China’s demand needs, since China takes 35% of Russia’s exported oil.

It would also add to world supply and put downward pressure on prices in the future.

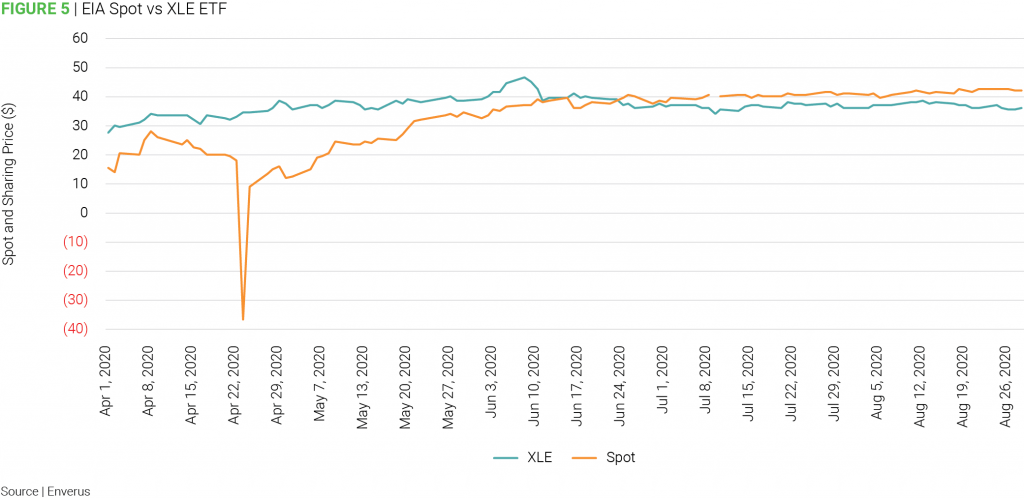

Like most folks in the patch, I’ve always thought that rising prices would translate into improvements in public equity prices. However, as I’ve checked oil and gas equity prices against spot prices, I’ve seen a curious inverse relationship when oil prices quoted in the financial markets go up, the public equity values seem to go down. Below is a graph of Energy Information Administration spot prices versus the XLE ETF closing price from late 2019 through today.

As COVID-19 concerns attributable to the rising death rates from late March to early April 2020 ramped up, the equity values in the XLE ETF seemed to shrug off demand destruction worries, even through the day spot prices blasted into negative territory.

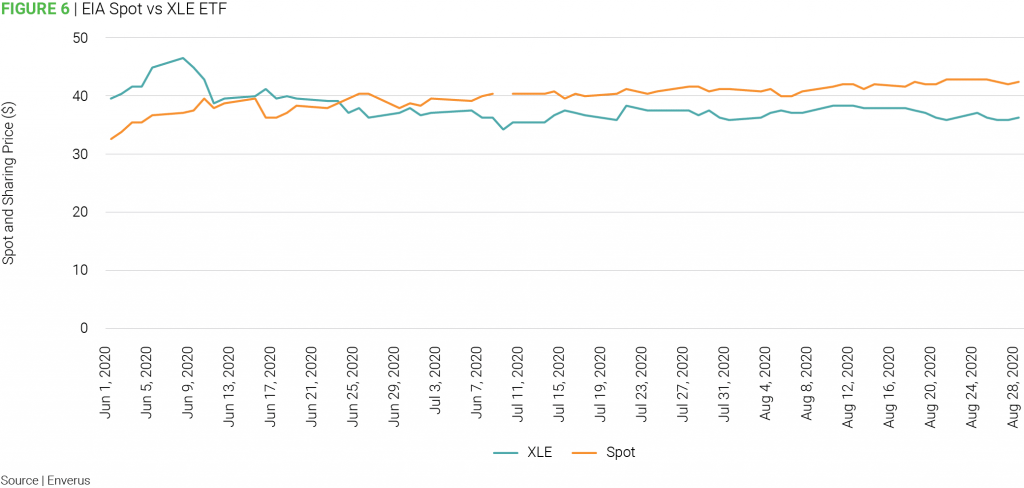

Starting in mid-June, however, there has been a disconnect. As spot prices have risen, the equities in the XLE ETF have lost ground.

Is the market afraid that improving prices will increase supply and essentially act as a choke on future price moves?

One thing seems certain — the truths we count on today may turn out to be the lies of tomorrow.