Two weeks ago, the world continued to be awash in oil due to the success of the domestic U.S. unconventional revolution and the recent production increases in Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Then, OPEC+ instituted a production cut of 9.7 MMbbl/d.

Prices went up … a little.

Then, on April 16, the International Energy Agency predicted larger than expected demand weakness due to COVID-19 effects on world markets.

Prices headed south.

On April 17, ConocoPhillips, Occidental Petroleum, and Chevron announced production cuts that together totaled about 410,000 BOEPD, or about 3% of the total U.S. daily output.

Shares of Conoco surged 13%, and most other publicly-traded companies in the oil and gas sector showed similar gains.

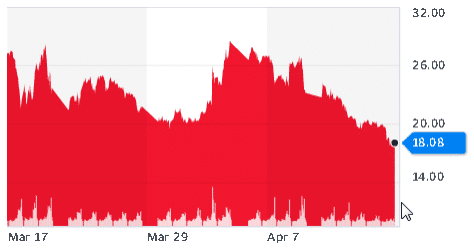

But West Texas Intermediate (WTI) traded at nearly $18 per barrel, nearly $2 down from the previous close.

Posted prices, as reflected in the Plains All American Pipeline 2020-074 Crude Oil Price Bulletin, were $14.25-$14.75 for WTI, and $8.50 for South Texas Sweet.

The broader market then rallied, based on hope the country will “open up” and expectations that the encouraging, but as yet anecdotal, clinical trials conducted by Gilead Sciences for its antiviral drug remdesivir will soon lead to a rollout of an effective COVID-19 treatment.

Then, the hammer hit.

In just under three weeks, we’ve seen a nearly 70% price collapse in the world’s most important commodity.

According to data from Plains All American Pipeline, producers were suddenly required to pay the gatherer to take oil away from their leases.

“The Twilight Zone” just got real.

There was some strengthening of Henry Hub gas futures, according to data from CME Group. This is because of the weakness in oil, but looking out to August 2021, prices quoted are in line with an average of about $2.25-$2.50 per MCF.

One of my favorite movies is “The Firm,” based on John Grisham’s novel.

Tom Cruise plays the part of a recently graduated lawyer who unwittingly joins a law firm that is closely tied to the mob. He becomes more aware of his firm’s corruption as he realizes he and his wife are being closely monitored by his employers. He tells his wife Abby he hasn’t found a way out, but maybe has instead found a way through.

What I propose may not be the answer, but it’s worth considering. For some operators, it may be a way through.

Convert those BTUs in your natural gas and oil to power and free them from the shackles of an unstable oil pricing market.

The oil & gas industry deals in a commodity that is subject to the whims of commodity markets and multiple fractionated and volatile sources of supply.

The amount of CAPEX our industry spends is enormous, especially when compared to FANG stocks such as Microsoft, Google, or Amazon.

The disconnect between market cap valuations of companies that produce a good and can therefore control their pricing, yet only dedicate a portion of their market cap to CAPEX versus the oil & gas industry, is really jarring.

Pouring these sums of money into a highly volatile pricing hopper has got to be an exercise in faith and optimism.

The demand for power, however, is constant, and it’s not typically dependent on the whims of foreign oligarchs or dictators.

The chart below shows ERCOT’s real-time prices for the period from Feb. 24, 2019-Feb. 24, 2020. Note the seasonal offset in price spikes between North and Houston Hub.

Obviously, there are periods of the year when the revenues that can be realized for the sale of power dwarf the revenues from selling gas to a gatherer.

The price per MWh is highly dependent on the hour of the day. You can see this in this two-day graph prices for Aug. 15-16, 2019.

At peak usage times power was selling for $1,700-$3,500 per MWh.

Intrigued, I did a rough model of comparative revenue generated between selling natural gas to a gatherer, with the revenues to be gained from power generation.

I want to give a shout out to Matthew Crawford and Travis Simmering of Dynamis Power Solutions who helped with the following gas turbine stats.

A large gas turbine can generate 35 MW of continuous power. The most recent generations have been used for pressure pumping applications but have had a side benefit of reducing power grid costs when power gets pricey.

It will need about 6 MMCFD of dry gas with at least 1,000 BTU/MCF to operate at peak efficiency. So I pulled a well that was producing during the time period I had ERCOT pricing and compared revenues realized from selling gas at a presumed price of $2.25 per MCF versus prices realized from powering a turbine and selling power to the grid.

Here’s what I modeled by taking one well and calculating its revenues from either selling all produced gas to a gatherer—business as usual—or instead dedicating the required amount of gas to fuel a turbine to generate power for sales to the grid.

The hybrid model assumes that enough produced gas is diverted to the turbine to deliver 6 MMCFD, or 180 MCF per month, and the remainder gas is sold by normal means to the gas gatherer.

Note that in some months revenues from just sale to the grid lag revenues from sales to a gas gatherer, and vice versa.

The revenues are gross revenues and do not account for mineral royalty or severance tax.

But look at this table.

The total revenues from the hybrid model are almost double those achieved from “business as usual.” This model was run on wellhead prices of $2.25 per MCF, but the hybrid model still outperforms the “business as usual” model even at $4 per MCF.

Given that the switch-on cycle times for these turbines is a matter of minutes, gas apportionment can be very targeted to projected power demand.

How many wells in Texas can produce the required amount of gas? There are 371 gas wells in Texas producing 180,000 or more MCF per month.

Given the cost of turbines—close to $20,000,000—there are probably a limited number of companies that can purchase these things. But they can be leased, and since they are mobile, they could be pressed into service to generate revenue once produced gas has dropped below the required supply levels.

There are smaller, more cost-efficient units that require less gas, but these produce less power.

Although partnering up in the oil patch is still a bit of a lost art, there are 4,007 wells in the U.S. currently making 3,000 MCFD or more.

What’s to stop smaller operators from joint venturing into a business model where they jointly finance a turbine and sell power?

It’s certainly not a slam dunk proposition to do this.

Gas contracts have to be to honored and fulfilled or modified.

Mixing of lease gas from separate leases would have to be done in ways that respect mineral owner’s rights—and the mineral owner’s share of the revenues derived from burning their gas for power would have to be negotiated.

As wind generation takes more market share, the power markets will probably become more volatile over time—and maybe power prices will drop. Alternatively, if federal tax credits for renewables are not renewed, supply to the grid from alternatives may slow down, keeping the current pricing structure roughly intact.

On the other hand, if electric vehicles take more market share from gasoline-powered forms of transport, power prices might rise.

But for operators struggling with their gas revenues … and maybe losing a fair bit of money due to flaring, it’s worth considering.

As Tom Cruise’s character in “The Firm” suggests, “It may be a way through.”

Next time around I’ll look at oil-fired cogeneration turbine power.

Have a thought you’d like to share? Send it to me at [email protected].